Do It, but Don’t Over Do It 0

The Dynamics of Demonstrated Interest

By Eric Hoover

This year, American University received a record 17,000 admissions applications, a 13 percent increase over last year. With quantity came quality: by various statistical measures, the university will admit its most accomplished, most diverse class ever this fall. And American’s admit rate fell to 43 percent from 53 percent this year.

This year, American University received a record 17,000 admissions applications, a 13 percent increase over last year. With quantity came quality: by various statistical measures, the university will admit its most accomplished, most diverse class ever this fall. And American’s admit rate fell to 43 percent from 53 percent this year.

In the numbers-driven realm of admissions, all this is good news, a sign of rising fortunes. But it’s also a complicated development. For one thing, applications have swelled at so many selective colleges that the meaning of such an increase can be difficult for a given admissions office to interpret (increases this year could portend increases next year-or not). Moreover, as colleges become more selective, they often find themselves competing with institutions a rung or two higher on the ladders of selectivity and desirability, at least for the top students.

Although there is prestige in this kind of association, there is also uncertainty. How many applicants would turn down a super-selective, big-name college to attend a somewhat less-selective, less-famous one? How do you know whether a student considers your college a top choice or a “safety school”? How does an applicant’s sense of “fit” with a college relate not only to matriculation, but also retention?

In recent years, such questions have prompted American’s admissions team to look more closely at “demonstrated interest,” the popular term for the contact students make with a college during the application process, such as by visiting the campus, participating in an interview, or e-mailing an admissions representative. In theory, it’s a way to measure the likelihood that an applicant will matriculate-and succeed if they do.

The practice is not new, but its importance has grown at some selective colleges in this era of ballooning applications and economic uncertainty. From 2003 to 2006, the percentage of colleges rating demonstrated interest as a “considerably important” factor increased to 21 percent from 7 percent, according to an annual survey by the National Association for College Admission Counseling. Since then, that number has held steady (another 27 percent of colleges now deem it “moderately important”).

That number may well grow as more colleges contend with complicated enrollment challenges in the coming years. “This is an educational enterprise, but it’s also a business enterprise – we have to bring in a certain number of students,” says Sharon M. Alston, American’s executive director for enrollment management. “It’s getting harder and harder for colleges to know who’s going to come.”

That is why American tells prospective students the following: If you really like us, let us know.

Recently, American has created more opportunities for students to do just that. The admissions office has broadened its recruitment strategies to include online chats for prospective applicants. Participation is noted in each student’s file.

This year, American added more regional information sessions in key markets. It reinstated its overnight visit program. It significantly increased the number of admissions interviews it conducted. It added an old-school touch – a print letter, instead of an e-mail, inviting families to particular events.

Meanwhile, American sent more e-mails to high-school students than ever before, starting with a message that directed them to a revamped admissions Web site. One follow-up message was self-consciously humorous: it acknowledged that students were probably tired of getting so many messages from colleges, and that studies had shown such barrages killed brain cells. Embedded in the e-mail was a link, of course. That message alone prompted over 1,000 students to engage the university.

Demonstrated interest often dovetails with another strategy for managing uncertainty: the waiting list. This year, American offered a spot on its waiting list to about 2,000 students, a seemingly large number considering that the university had accepted approximately 7,300 students for its freshman enrollment target of 1,450.

Applicants who received waiting-list invitations from American fit a range of descriptions. Some were less competitive than the applicants the university accepted, but others were top-notch students who did not seem like a good fit for the university. In some cases, the reason was a lack of demonstrated interest, Ms. Alston says.

Applicants who received waiting-list invitations from American fit a range of descriptions. Some were less competitive than the applicants the university accepted, but others were top-notch students who did not seem like a good fit for the university. In some cases, the reason was a lack of demonstrated interest, Ms. Alston says.

As some admissions officers will tell you over coffee, the waiting list is a sure way to manipulate enrollment outcomes, as well as enrollment statistics. A selective college might make waiting-list offers to super-qualified applicants it deems unlikely to enroll, for whatever reason. This is one way to lower admit rates and preserve “yield,” the percentage of accepted students who enroll.

Greg Grauman, American’s director of admissions, says that he is much more concerned about fit than statistics, however. For one thing, American has seen a high correlation between retention and demonstrated interest. He explains that the use of a waiting list, coupled with a consideration of demonstrated interest, helps him shape a class of students who are the most likely to thrive at AU.

And that means wait-listing some applicants who look superb on paper. “In years past, when we had fewer applicants, we may have been more likely to admit that student,” Mr. Grauman says. “Now we have more flexibility.”

And that’s one illustration of how admission outcomes have become more uncertain at selective colleges. “People are used to the Harvards, Yales, and Princetons of the world being unpredictable,” Ms. Alston says. “The kid with the 4.0 grade-point average and the 1600 SAT score wasn’t necessarily guaranteed a spot at Harvard, but you knew at least that he was definitely guaranteed admission at American.”

The erosion of those certainties can prove startling to high-school counselors. “Students who would have otherwise been accepted to all or most schools on their short list are being wait-listed more than I ever remember,” says Jay Bass, director of counseling services at Thomas S. Wootton High School, in Maryland.

Mr. Bass advises his students to reach out to colleges they like, both to demonstrate their interest and to help them decide if the campus is right for them. “The syndrome of just applying to as many schools as possible without a focused approach,” he says, “is of little value to students or colleges.”

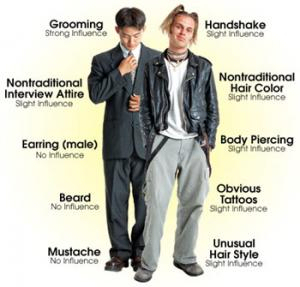

The trick is that interest can be feigned. Monica C. Inzer, vice president and dean of admission and financial aid at Hamilton College, in New York, says her staff has dealt with students who profess their love for the college, only to turn down an eventual offer. “Some students are really good at packaging themselves,” she says.

Nonetheless, Ms. Inzer believes Hamilton’s consideration of demonstrated interest is important, for the college and applicants alike. For one, she wants applicants to visit the campus to understand that the college is on a hill surrounded by cornfields. “I don’t just want them to enroll,” she says. “I want them to be happy and graduate.”

Ms. Inzer describes demonstrated interest as something that tends to tilt decisions for students on the margins. “I care more about demonstrated disinterest than demonstrated interest,” she says.

Recently, Hamilton’s admissions staff took a closer look at how they deal with a crucial component of the demonstrated-interest equation: the interview. Hamilton’s Web site strongly encourages applicants to schedule an interview, stating that those who do not “will be at a competitive disadvantage in the admission process.”

Recently, Hamilton’s admissions staff took a closer look at how they deal with a crucial component of the demonstrated-interest equation: the interview. Hamilton’s Web site strongly encourages applicants to schedule an interview, stating that those who do not “will be at a competitive disadvantage in the admission process.”

Yet Ms. Inzer and her colleagues decided that the wording was too strong. After all, Hamilton admits plenty of qualified applicants who have not shown strong interest in the college, via an interview or anything else.

So Ms. Izner rewrote the passage to convey that the interview is not just an another admissions hurdle to clear, but a meaningful part of what could become a lifelong relationship with the college. “That relationship,” the new wording says, “begins with an interview.”

Despite the prevalence of demonstrated interest among selective colleges, some enrollment experts are skeptical of popular measures of an applicant’s likelihood of enrolling.

“A lot of institutions aren’t doing a sophisticated analysis,” says Richard A. Hesel, a principal for Art & Science Group, a firm that specializes in strategic marketing and planning for colleges.

Mr. Hesel has found that other factors – such as a student’s SAT score, family income, and intended major – are often more predictive of enrollment outcomes than whether or not that student has visited the campus or called to ask a question. In other words, demonstrated interest may just tell you something that you already know.